With our country with its food safety, consumer suspicion and fear

BEIJING, March 27 (Xinhua) — “I am wondering what’s in this flour. Are there additives, and are they toxic or safe?” asked housewife Wang Jinghua as she shopped in an outlet of Walmart in southwest Beijing.

Wang told a Xinhua reporter she was worried about benzoyl peroxide, an additive widely used in flour, biscuits and other food. “A friend told me even a slight amount of this chemical is harmful, but I’m not sure what to do,” Wang said.

Her confusion is understandable. No single agency or ministry in China is solely responsible for food safety, and it’s often difficult for the shopper to know what’s allowed, what’s banned, and what’s safe. Labels sometimes contain correct but obscure chemical descriptions, which are confusing to the ordinary consumer. Packaging isn’t always safe, either.

Pesticides, industrial chemicals, excessive or banned additives and suspected carcinogens show up in many food products.

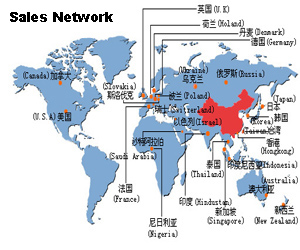

The safety of Chinese food isn’t just a domestic issue. With food exports of 31 billion U.S. dollars from January to November 2008, up 13.8 from the same period in 2007, Chinese produce, fish and dairy items, among other foods, are rapidly becoming part of the global food chain.

Supervising the industry is a huge undertaking. Statistics show that as of 2008, China had an estimated 500,000 “large-scale”, 350,000 small- and medium-sized food processing enterprises, and more than 20 million privately owned businesses that producing and selling food products.

Last year, authorities investigated an average of 200 fake food cases a day, which were mostly involved in small enterprises and businesses.

In response to these concerns and problems, China has stepped up its efforts to ensure food safety and quality, with new labeling laws and a Food Safety Law that will take effect June 1. The new law, among other provisions, calls for the State Council to establish a food safety commission but does not give a deadline for that.

PRETTY, BUT IS IT SAFE?

“Chinese people traditionally favor ‘good-looking food’ and a substance like benzoyl peroxide makes flour-based products look white and tasty, as it bleaches wheat’s natural yellow color,” said Chen Junshi, a member of the Chinese Academy of Engineering.

“It is simply called ‘wheat bleaching’ in Chinese, but this is a misunderstanding,” he said. “Benzoyl peroxide is not only used to make the flour appear white. It also plays an antiseptic role.”

Under Chinese food additive regulations, the maximum volume of benzoyl peroxide is 0.06 grams per kilogram. Regulations vary elsewhere. Canadian rules limit the content to 0.15 gm, but the European Union banned its use in food several years ago.

Benzyol peroxide has non-food uses, too: according to the U.N. Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), it is also used in the manufacture of plastics, a curing agent for silicone rubber, and a component of treatments for skin disorders.

Also according to the FAO, there are possible side effects of benzoyl peroxide in foods: the formation of harmful degradation products, the destruction of essential nutrients and the production of toxic substances from the food components.

Benzoyl peroxide is one of the around 1,700 additives that China allows to be used in food products.

CONSUMERS WONDER, WORRY

Surveys reflect the concern of the Chinese public over food safety. In 2006, the State Administration of Grain held an online survey, and about 87 percent of those responding said they didn’t want to buy food with bleached wheat.

Other, later polls from a variety of sources indicate continued, broad concern over food safety:

— A 2007 survey by U.S.-based consulting company ATKearney found more than 95 percent of 1,500 Chinese questioned ranked food safety as “very important” in 2007.

— In March 2008, China’s Ministry of Commerce said another survey found that 97.2 percent of urban residents ranked food safety as a major concern. Even among rural residents, who tend to have lower incomes and fewer sources of information, 86.1 percent responded that they put food safety among their major concerns when shopping.

— In December 2008, a telephone survey of 300 Chinese consumers by U.S.-based IBM found that “over the last two years in China, distrust with food retailers and manufacturers has grown even more” than in the United States and Britain. IBM said 84 percent of respondents claimed they had become more concerned about food safety over the previous two years.

“It’s just difficult for me to believe that food with [benzoyl peroxide] is 100-percent safe. Instead, I would rather be more cautious,” Wang said: “The problem is I can not tell whether the food ingredients listed on the label are believable.”

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

Although the Ministry of Health maintains a list of food additives on its website, many Chinese consumers, like Wang, complain it’s hard to know whether their food contains additives or other harmful substances, as the labels are often “confusing”.

Zhang Jun, who does chemical research at a Beijing-based institution, said he always pays attention to labels, but most of his friends find it hard to know what the labels mean.

Some companies, he said, list additives by their chemical equation or scientific name, which puzzle consumers.

“I often tell my friends that potassium sorbate is an antiseptic and people should avoid eating it,” he said. Potassium sorbate is used to prevent spoilage. “But, the question comes: who can assure us there is no antiseptic in the product if the company did not put it on the label?”

China adopted a food-labeling regulation in last September, which requires producers to specify names and amounts of additives in food. Those who violate this regulation face fines of 5,000 yuan to 10,000 yuan.

“Moreover, there is no effective way for consumers to know which additive is safe and which is toxic,” Zhang said

Zhang also criticized the widespread practice of having film and music celebrities endorse food and medicines in advertising.

“People are always prone to trust stars and will not doubt their word. But some famous people take advantage of consumers’ trust,” he said.

Qiu Baochang of the Beijing Lawyers’ Association told Xinhua:” The government should call a halt to the practice of celebrity endorsements of food, to protect the rights of consumers and the stars’ reputations.”

Beijing Consumers Association Secretary-General Zhang Ming agreed, saying: “These stars actually seldom try the products they endorse.”

LOOPHOLES EVERYWHERE

The major problem was the use of banned substances, such as melamine (an industrial chemical used in plastics) and Sudan red (a dye used in oils, waxes, gasoline and shoe polish).

At the Sixth China Food Safety Annual Meeting held last August, China National Food Industry Association Chairman Wang Wenzhe said that the county’s food quality had improved greatly in recent years. But he also acknowledged that food quality was far below consumer expectations, with many cases of excessive pesticide residue and banned food additives.

Ma Yong, a senior official with the National Food Industry Association, told a food-quality seminar in Beijing on March 13 that problems can occur at every step, including production, raw materials, animal feed, planting, slaughtering, processing, transportation, packaging and sales.

There have been many cases of banned and dangerous substances turning up in a wide variety of food.

In 2005,Sudan red was found in salted duck eggs in some provinces and cities. It turned out that poultry farmers were giving hens and ducks the chemical to make the yolks of their eggs red, which commands higher prices.

A year later, several fish farms in eastern Shandong Province that were raising turbot, a popular type of flatfish, were fined and ordered to halt sales after traces of carcinogens including malachite green were detected in samples. Malachite green is an anti-fungal agent for aquarium fish, but it’s not supposed to be used for fish intended for human consumption.

Packaging can be a particular problem if it doesn’t protect the food or contains harmful substances.

“In some developed countries such as the European Union and the United States, producers can face severe punishment if there are problems with the packaging, but China has no strictly enforced packaging requirements,” Zhu Tiancheng, a lawyer with Beijing Jindong Law Firm told Xinhua.

Liu Yonghao, the board chairman of farming company New Hope Group, told Beijing Sci-Tech Report earlier this month that food companies should reduce safety risks by better monitoring of the whole production and distribution process, from raw material to sales.

“Although it requires a huge investment to establish an entire monitoring chain, it is good for a company in the long run,” he said.

THE HUMAN TOLL

According to the Ministry of Health, there were 431 food poisoning incidents reported in China last year, causing 13,095 illnesses, and 154 deaths.

Then there was the scandal that broke last September, in which dairy products, including baby milk powder, were adulterated with melamine. At least six Chinese infants died and almost 300,000 developed kidney problems and other symptoms.

In this case, the former board chairwoman and general manager of the Sanlu diary group, Tian Wenhua, was sentenced to life in prison. Earlier this month, eight senior government officials from food quality supervision departments and agriculture ministry were fired or disciplined for supervisory failure in the scandal. Last year, the director of the General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine (AQSIQ) Li Changjiang resigned.

In mid-March, 15 people were arrested in the southern Guangdong Province on charges of selling pigs that had been given fodder containing banned additives — ractopamine and clenbuterol — which help pigs produce leaner pork. The latter chemical is banned as an additive in pig feed in China because it can be harmful and even fatal to humans.

TRADING PARTNERS ACT

The milk scandal had a swift impact on China’s dairy product exports. The General Administration of Customs said these shipments dropped 10.4 percent last year to 121,000 tonnes after the scandal made the headlines.

There has also been lost export business for small producers of cooked food, seafood, pet food and even medicine, when these companies found they could not meet the safety requirements of foreign countries.

The concerns reach far down into the local level. For example, Shunde City in Guangdong Province has been a major supplier of eels. However, the city saw its exports plunge last year after overseas consumers, especially in Japan, became worried about food safety.

In the first three quarters of 2008, exports fell 66 percent by volume and almost 53 percent by value. Shipments to Japan, the single largest overseas buyer of Shunde’s eels, fell 61.2 percent.

Last November, United States Department of Health and Human Services opened offices of its Food and Drug Administration in Beijing, Guangzhou and Shanghai, the first outside the United States, as “a part of an ongoing strategy to continually improve import safeguards.”

Experts said this move reflected the concern of other countries about the safety of Chinese food.

“Once a time, ‘Made in China’ products are losing trust in overseas markets,” said Zhu.

IMPORTS CAN ALSO BE DANGEROUS

Experts warned that problems in the inspection and quality system in China were also exposing Chinese consumers to unsafe imported food. For example, in December, China suspended the import of Irish pork products and animal feed after the products were suspected of being tainted with dioxin, a chemical derived from petroleum, which is thought to be harmful to humans.

China’s quarantine inspectors detained about 312 tons of Irish pork products, but by then another 93 tons had already made their way into the market.

Ge Zhirong, a former AQSIQ director, told Beijing Sci-Tech Report this month that the government should introduce new regulations on import/export food safety supervision and management.

“That would safeguard the rights of both domestic consumers and overseas consumers,” he added.

GOVERNMENT EFFORTS

In addition to the labeling law introduced in September, the Chinese government has made other safety efforts.

In February, China approved a Food Safety Law, which states that “only those items proved to be safe and necessary in food production are allowed to be listed as food additives.”

The law, which will take effect June 1, says food producers may only use additives that have been approved by the authorities. Companies that break the law face possible temporary or permanent closure, the latter through the loss of production licenses in serious cases. The law also:

— requires food producers to follow safety standards when using pesticide, fertilizer, growth regulators, veterinary drugs, animal feed and feed additives, and to keep farming or breeding records.

— gives consumers whose health is affected by unsafe food the right to claim losses of up to 10 times the purchase price from manufacturers or retailers.

— regulates ads, stating that “social institutions, organizations and individuals are forbidden to recommend food products in deceptive advertisements” at the risk of unspecified damages.

— sets up a recall system, under which producers must recall food that fails to meet national standards immediately, while retailers must stop sales of “problem food”.

— makes the Ministry of Health responsible for assessing and approving food additives and regulating their usage.

On March 6, the Ministry of Health issued a circular to its local offices, urging them to step up prevention of food contamination and monitoring of food quality-related illnesses. The circular covered 16 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities where food problems have been most prevalent.

At the same time, Health Minister Chen Zhu said the ministry would create a national database covering food contamination and food-borne illnesses within two years. He also ordered hospitals and other health organizations to report food poisoning and other food-related illnesses promptly.

BETTER, BUT NOT GOOD ENOUGH

Professor Zhang Xi’an of Northwest University of Politics and Law in Shaanxi Province told Xinhua: “The law was a new push to improve food safety through stricter monitoring and supervision, tougher safety standards, recall of substandard products and severe punishment for offenders.”

“Most companies do a good job of ensuring food safety, but some small companies still fail to produce safe food,” said Zhu of the Beijing Jindong Law Firm.

“But as far as I know, only a few companies have been punished, because government supervision was not as strict as expected. The government should play a more active role in safeguarding the market,” Zhu said.

“Most consumers only learn about food problems from the media. It isn’t fair to the people,” he said.

Zhu suggested that the government conduct more frequent and stricter inspections nationwide, to expose risks, crack down on illegal activities and protect consumers’ rights.

“On the website of the Ministry of Health, there is a document listing all the food additives approved by the government. Consumers should study it carefully to protect their health,” he said.

TOO MANY SUPERVISORS

Zhang said the “root cause” of China’s food safety problem is that the country “lacks a central administrative body to manage food safety.”

He said: “There are too many government bodies involved with food safety, including health departments, drug and food safety bodies and others.

“These bodies share licensing and inspection duties, and many of the duties overlap. Even worse, some of the rules for producers contradict one another, so some companies can take the advantage of loopholes in the regulatory system.”

On March 5, Premier Wen Jiabao said in the 2009 government work report to the annual legislative session that China would step up the fight against unsafe food.

China Health Care Association secretary general Xu Huafeng told Xinhua this statement reflected the understanding that the government “can’t sit still.”

CONSUMERS WANT ANSWERS

As for ‘wheat bleaching’, the Ministry of Health launched an investigation in December into whether benzoyl peroxide was harmful to humans and what quantity, if any, should be allowed in food.

According to media reports earlier this month, the ministry indicated that experts were still investigating the issue. It didn’t say when the results would be available.

Luo Yunbo, Vice Chairman of the Chinese Institute of Food Science and Technology (CIFST), a non-profit academic institution, said: “The investigation is a complex process that requires several tests and experiments, and the result is not likely to come out soon.”

Luo said officials and experts should take a scientific attitude towards the experiment. They should neither demonize food additives nor conceal the truth about them.

“Whatever the result, the ministry should tell the public quickly. Industry development should not call for a sacrifice of the public interest,” he added.

CURIOSITY IS POSITIVE

Hou Caiyun, a food expert with China Agricultural University in Beijing, said it was a good sign that consumers had become more cautious about food quality, which reflected social and economic development.

“However, people should look at food additives correctly. Excessive panic should be avoided,” she said. Banned substances such as melamine and Sudan red were one thing, approved additives were another.

She said: “Minimal amounts of benzoyl peroxide aren’t harmful to human health, at least according to the tests so far, because this substance can be digested and excreted.

“This doesn’t mean that enterprises can add the substance at random. They should strictly abide by the country’s regulations,” she added.

Hou suggested that the government encourage consumers to change some of their eating habits and enjoy “green food”.

She said: “People should shift their emphasis from appearance to food quality.”

Hou said China’s flour industry and food processing technology have matured sufficiently to produce food that is “nice-looking” and tasty, without additives.

“In the long run, food additives will be used less and less,” she said.

Leave your response!