No milk: dairy ingredients behind the crisis

I have no idea what it would feel like to be a dairy farmer. I don’t run a business that was started by my father or mother or grandparents, or that I built myself; I don’t own and manage land that has been in my family for generations. Come to think of it, I’ve never really had to make a major business decision, let alone a decision that could determine my family’s future and the future of animals I raise and care for.

I can’t claim to know what it feels like to be a dairy farmer, but that doesn’t make the recent conversations I’ve had with dairy farmers any easier.

The Associated Press reports:

Hundreds of thousands of America’s dairy cows are bring turned into hamburgers because milk prices have dropped so low that farmers can no longer afford to feed the animals…. Dairy farmers say they have little choice but to sell off part of their herds for slaughter because they face a perfect storm of destructive economic forces.

Or, in the words of the Minnesota farmer I talked with on Friday, “This could be it – this could really be it. What are we going to do?”

There’s been a fair amount of press coverage of the dairy price crisis that began last fall, from January’s widely-circulated New York Times article to the daily headlines in many dairy-producing regions. Milk prices currently cover less than half of farmers’ production costs, and there’s no end to the drop in sight. In California, debt-ridden dairy farmers are committing suicide; elsewhere, they’re pouring milk down the drain, wringing their hands, and hoping for a miracle.

Fluid milk isn’t the only product at rock-bottom prices. As Andrew Martin reported in that NYT article, the price of U.S. milk products used by processors to make other dairy foods – things like nonfat dry milk powder, which goes into everything from baby formula to pizza cheese – has also dropped, falling by nearly 65% since mid-2007.

The reason for this drop, we’re told by Martin and others, is that the recession has created a surplus of milk and milk products. Cows keep producing, but consumers aren’t buying – here or anywhere else in the world.

It’s interesting, then, that at the moment demand was supposedly crashing hard – the last quarter of 2008 – U.S. dairy imports rose by more than 15% over the previous three quarters. If no one in the U.S. wanted milk, then why did companies increase their spending by nearly $120 million last fall to bring it in from abroad?

According to one farm group, the answer can be told in the form of a story with four main characters: a sneaky company (or, OK, several), a misguided media, a useless regulatory agency, and an ingredient commonly used to make glue that may be in more dairy products than we know. Intrigued? So was I.

Last week, the National Family Farm Coalition, whose members include small and mid-sized dairy producers from the Midwest, Northeast, and upstate New York, held a press conference on “the real cause of the dairy price crisis.” Their thesis: it’s not because U.S. farmers are producing too much or because demand is falling precipitously. No, some very different culprits are to blame. I’m going to focus on one, a product called Milk Protein Concentrates, or MPCs.

(A note: I’m leaving out the other factors because they involve the way that milk is priced, which is mind-bendingly technical. If you’re into that, I recommend reading the press release and this analysis [pdf] by John Bunting, a NY dairy farmer, editor of The Milkweed, and dairy policy guru.)

Chapter 1: The ingredient

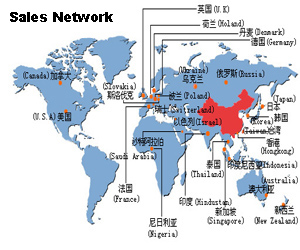

Milk protein concentrates are created when milk is ultra-filtered, a process that drains out the lactose and keeps the milk protein and other large molecules. The protein components are then dried and become a powder. That all sounds relatively benign – until we learn that those “other large molecules” can include bacteria and somatic cells; that virtually all MPCs come from other countries, most of them with very poor food safety records (China, India, Poland, the Ukraine); and that the milk used to make MPCs is usually not cows’ milk. More often, it is from water buffalo, yaks, or other animals common to the countries where MPCs are manufactured.

Perhaps because of MPCs’ sketchy origins, they have never been approved as a food ingredient by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (They are, however, a common ingredient in some brands of glue.) The FDA has a list of additives it allows in processed food – the GRAS list, for Generally Recognized as Safe – and MPCs ain’t on it. That means the FDA hasn’t carried out safety tests on MPCs, as the law requires for any additive on the GRAS list.

I was therefore surprised to learn that MPCs are widely used in dairy products manufactured and sold in the United States. Kraft Singles have them, as did most other brands of processed cheese slices that I checked in the grocery store last night. Some snack foods, coffee creamers, candies, and nutritional drinks have them. They’re not approved by the FDA as a food ingredient, but they’re in a whole lot of food.

Chapter 2: The companies

We will put aside for the moment the question of why the FDA is allowing food processors to lace their products with unregulated dried yak’s milk from Siberia. Instead, we’ll ask why companies are going to such lengths to get their hands on the stuff – and what it means for U.S. dairy farmers.

From what I’ve heard and read, there is one major reason for the shift from home-grown moo-cow to imported who-knows-what: MPCs are much cheaper. Syndicated columnist Alan Guebert called it in a 2005 column, reprinted here on the website of Family Farm Defenders: “[It’s] about money. Money processors hope to make by outsourcing milk and dairy product ingredients, like cheaper MPCs, from New Zealand, India and other dairy exporters. Money processors can save by substituting cheaper, imported MPCs for pricier, unaltered American milk in their bottling and dairy product plants.” And substitute they did. Between 2004 and 2008, U.S. imports of MPCs increased by more than 300%. Just in the third quarter of 2008, MPC imports jumped 40% over the previous quarter.

A secondary factor driving the MPC stampede was the low-carb craze. (It’s always fun to blame things on Dr. Atkins, isn’t it?) Recall that the first step to making MPCs is the ultra-filtration of milk, which separates lactose from the protein, which is then dried. Lactose contributes most of milk’s carbohydrates, so MPCs are extremely low in carbs. As dairy processors sought lower-carb ingredients for their Atkins-friendly inventions, they found that MPCs fit the bill – and saved money, too. So in yet another example of the insanity induced by diet marketing, U.S. consumers turned up their noses at natural dairy products in favor of parched, parsed protein from unregulated foreign mammals. You gotta love nutritionism.

Chapter 3: The regulators

Dairy processors are pushing the USDA to change the formal definition of fluid milk, yogurt, and ice cream to allow the addition of MPCs. (Currently, something labeled “milk” must be actual milk from an actual cow, not rehydrated water buffalo protein.) They also petitioned the FDA to allow ultra-filtered milk, the substance that’s dried and becomes MPCs, to be used in cheese. They haven’t been successful yet thanks to protests from farm and consumer groups – you can read comments to the FDA on the ice cream proposal from Wisconsin-based Family Farm Defenders here – but in the meantime, the companies continue to use the ingredient anyway, and the FDA does nothing. NFFC has petitioned the FDA to start enforcing its own food safety laws regarding MPCs, but the group has not received a response.

The final chapter: The farmers

When companies import MPCs and use them in place of U.S.-produced powdered milk, or when they seek to allow them in dairy products that usually contain U.S.-produced fluid milk, those companies save money. U.S. dairy farmers end up where they are right now – out of business, or getting there.

The influx of low-priced “dairy” ingredients doesn’t seem to have made life easier for consumers, either. Although farmers saw their incomes drop by 50% in the past few months according to some reports, the USDA reports that the price of dairy products at the grocery store has fallen only about 7% since last summer’s high.

There are some proposals out there for what could be done to help struggling U.S. dairy farmers, but the ones actually under consideration by Congress have nothing to do with cracking down on imported MPCs. Instead, most of them involve the government buying up surplus U.S. milk to prop up market prices for farmers. That’s fine as far as it goes, and in the short term, it’s important. But if dairy companies continue to import MPCs willy-nilly and use them in place of domestic milk, then we won’t have actually fixed the problem. Instead, we will have created a Rube Goldberg solution whereby the U.S. government does just enough to keep some domestic dairy farmers in existence while allowing companies like Kraft to bypass them completely, and do so in technical violation of the law.

A better long-term solution to the MPC problem is FDA enforcement of the law, coupled with legislation like that offered last week by New York State Senator Darrel Aubertine, which would prohibit dairy processors from labeling products that contained MPCs as “dairy products.” Says the truth-speaking Senator:

We are a dairy deficit nation, but we’ve seen the price of milk drop to just about $9 per hundred-weight. [Cost of production is twice that.] Our farms are not going to survive if that’s all our farmers are getting for their quality product. We should not be letting foreign imports of milk and milk products hurt our dairy farmers and our consumers, since these imports are not regulated for quality and safety like in the United States. This bill would put New York in a position to make sure consumers are not misled into thinking they are getting real dairy products, when they can’t be sure of the origin or standards of the ingredients.

I’ll lift a glass of milk to that.

Leave your response!