FDA’s goal to deal with tender spices, so that security of supply

The Food and Drug Administration is reexamining the safety of a culinary staple found in every restaurant, food manufacturing plant and home kitchen pantry: spices.

In the middle of a nationwide outbreak of salmonella illness linked to black and red pepper — and after 16 U.S. recalls since 2001 of tainted spices — federal regulators met last week with the spice industry to figure out ways to make the supply safer.

Jeff Farrar, the FDA’s associate commissioner for food safety, said the government wants the spice industry to do more to prevent contamination. That would include using one of three methods to rid spices of bacteria: irradiation, steam heating or fumigation with ethylene oxide, a pesticide.

“The bottom line is, if there are readily available validated processes out there to reduce the risk of contamination, our expectation is that they will use them,” Farrar said. But the FDA cannot currently require it.

Legislation pending in Congress would require food companies to take steps, such as treating raw spices, to avoid contamination. The measure would also mandate that importers verify the safety of foreign suppliers and imported foods. The House overwhelmingly approved the bill last year, but it has stalled in the Senate.

Recent spice recalls have involved contamination with salmonella, a group of bacteria that live in the intestinal tracts of humans and other animals, including birds. Most healthy people infected with salmonella recover within days, but the illness can be serious and even fatal for small children, the elderly and those with compromised immune systems.

The ongoing outbreak of salmonella illness connected to black and crushed red pepper, which sparked a recall of those spices as well as salami products made with them, has been linked to 249 illnesses in 44 states and the District of Columbia. No deaths have been reported.

The long shelf life of spices and their widespread use make it difficult for health officials to detect an outbreak of illness and connect it to a particular spice.

Consumers often associate salmonella with poultry, meat and other moist foods. But microbiologists say that the bacterium can survive in dried spices for years and that it is tougher to kill in a dry environment.

Also, it takes only a small amount of salmonella in a dry environment to cause human illness, said Linda Harris, a microbiologist at the University of California at Davis.

Americans are eating more spices, consuming on average about 3.5 pounds in 2008, compared with 1.2 pounds in 1966, Agriculture Department records show.

Contamination of raw ingredients has long been a problem in the spice industry, according to Cheryl Deem, executive director of the American Spice Trade Association. “The vast majority of spices are cultivated outside of the U.S., where processing methods often result in contamination,” she said.

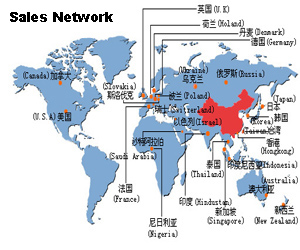

Except for red chili peppers, garlic and onions, most spices sold in the United States are grown overseas, including in India, Vietnam, Indonesia, Egypt, Grenada, Sri Lanka, Spain, Morocco, Turkey, Brazil and China.

In developing countries, many spices are harvested by farmers from small plots of land or grown wild and gathered from different areas, where pollution and water problems can create contamination hazards.

“You can import shoes, tables, lamps and chairs from anywhere in the world and you kind of know what you’re going to get,” said Paul Kurpe of Elite Spice Inc. in Jessup, Md. “But when you import food, you’re importing their habits, traditions and their standards of food safety.”

Some say the spate of recalls over the past decade does not necessarily mean the contamination problem is growing.

“In the last 15 years, food safety is just at an increasingly higher level of awareness,” Harris said. “We’ve got increased testing, increased detection methods. I don’t think what we’re seeing is necessarily a true increase in prevalence. I think it’s an increase in our ability to detect.”

Steve Markus, director of food safety and commercial products at Sterigenics Inc., the biggest food irradiation company in the country, said about half of the nation’s spices are irradiated.

But he said nearly all companies using irradiation sell to industrial customers. No retail spice company uses irradiation because federal law requires disclosure of irradiation on the label, and the industry thinks consumers will not buy those products.

“If the labeling issue would go away, I think there would be a high interest to go to irradiation,” Markus said, adding that irradiation is the cheapest and most effective method to decontaminate spices.

Roger Lawrence is vice president for quality control at Maryland-based McCormick’s, the world’s largest spice company. In its 121 years in business, it has never pulled a spice product from the market because of bacterial contamination, he said.

McCormick’s has built a comprehensive system that begins with educating its overseas growers about safe agricultural practices and ends with treatment of its finished product, he said. The company uses a mixture of steam treatment and ethylene oxide fumigation for the spices sold to retailers and irradiates only a small portion of spices for industrial customers at their request, he said.

Harris, who is scheduled to address the spice industry at its annual meeting next month, said her message is simple.

“With every outbreak, with every recall, you need to sit back, pull your food safety team together and look at what you’re doing, even if it’s to reassure yourself that you’ve got adequate controls in place,” she said. “The spice industry in its entirety should be reevaluating food safety.”

Washington Post Staff Writer

Leave your response!